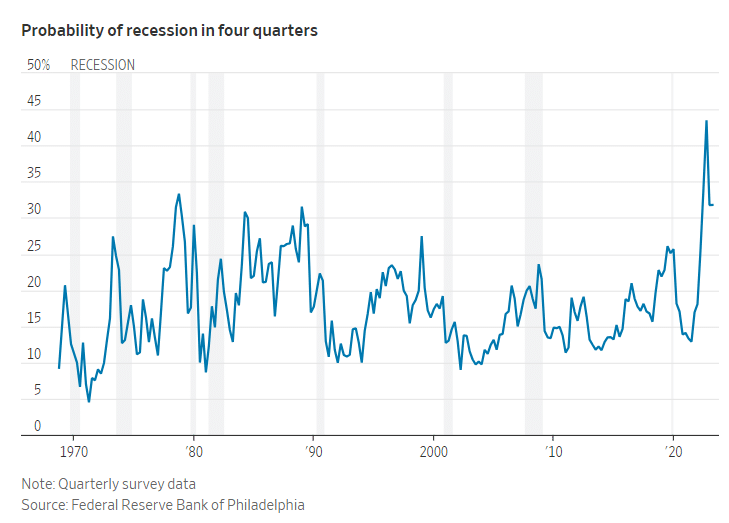

The 2023 recession is missing in action. At the end of last year, economists were more convinced than they’ve ever been that recession was on the way, but it refused to arrive. Now investors, economists and Federal Reserve policy makers are giving up on the idea, expecting the economy to be (a bit) stronger and stock prices and bond yields to be higher.

Why aren’t we in recession? Is it still on the way? And could it be that the recession forecasts perversely helped us avoid recession?

The recession didn’t arrive because we had two pieces of surprising good news. First, energy prices dropped, helping support demand, as Europe secured supplies to replace Russian gas more easily than expected.

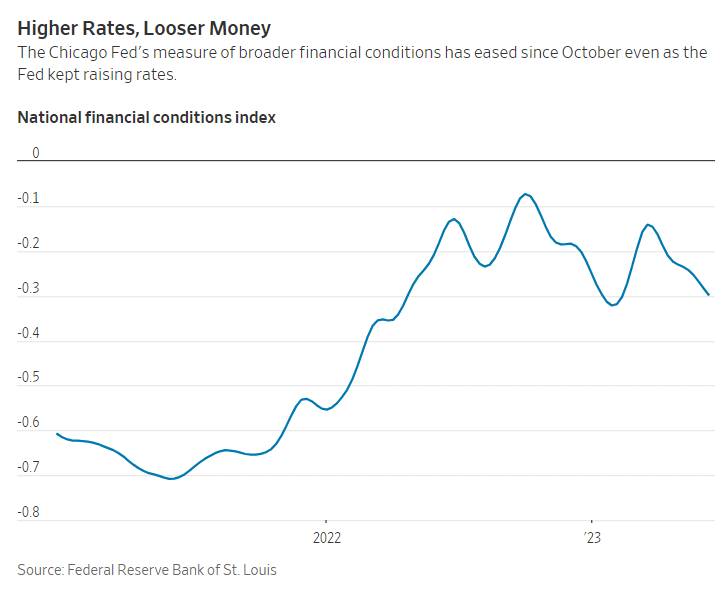

Second, the economy and the jobs market turned out to be far less sensitive to interest rates than economists thought, at least so far. Companies and consumers had locked in long-dated loans with low rates during the pandemic. Household savings piles took time to run down. And workers got big raises, more than inflation. All these factors supported consumption and business. Rebounding stock and credit markets and steadyish long-dated Treasury yields meant overall U.S. financial conditions have eased since October even as the Fed tried to tighten them.

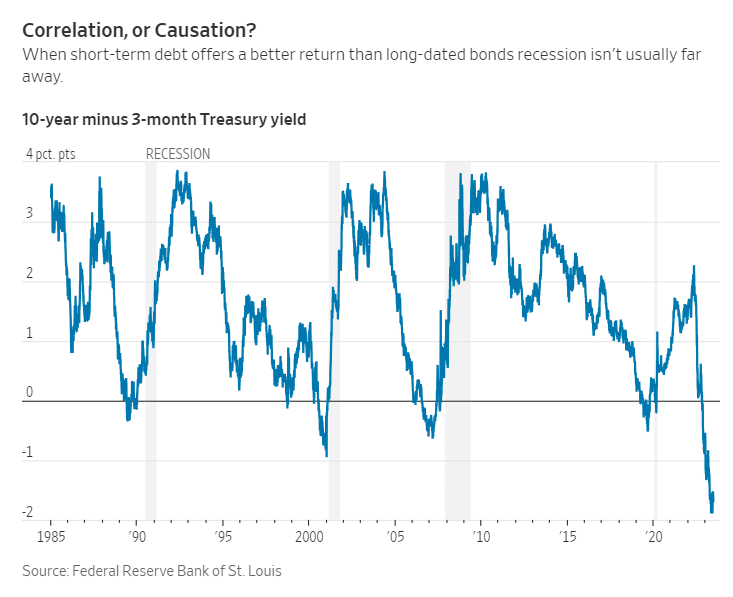

Many of these factors could reverse, as I discussed in my last column. But the biggest warning sign that recession has been delayed, not defeated, is that short-term interest rates remain well above 10-year Treasury yields, what’s known as an inverted yield curve.

An inverted yield curve tells us one thing with reasonable certainty: Investors don’t think the current level of interest rates can last. At some point rates bite, the economy slows, inflation comes down and the Fed cuts rates again. There’s a complication in that Fed holdings of long-term Treasurys may be suppressing their yields, but the basic point is that markets and most economists agree that at some point rates are going to come down again.

History tells us more: In the U.S., rates usually come down again because there’s a recession. But not always. In 1966 the curve inverted without signaling recession, although each of the next eight recessions was preceded by an inversion, with no more false signals. The yield-curve record in other major countries is much worse, with the U.K. inverting six times with only three recessions since the 1980s. (It is inverted again now.)

I find it hard to believe that the 2019 inversion predicted the pandemic, or that the 1973 inversion predicted the Arab oil embargo. In both cases, those keen on the yield-curve signal would have to argue that even without the surprise shocks there would have been a recession. Equally, the U.S. “recession” of 2001 never had the two successive quarters of falling gross domestic product that’s used as the definition for most countries; the U.S. goes by a broader view taken by a committee of eight academic economists instead.

Definitions matter, in part because no one really knows whether the economy is growing or shrinking, and frequent large revisions can change the story many years later. Use the income measure rather than the more-popular output measure of GDP—they ought to be the same—and the U.S. economy has shrunk for the past two quarters. Maybe the yield curve was right and we’re already in recession, but didn’t notice?

The yield curve may also have turned into a causal element as much as a predictive one. Campbell Harvey, a professor at Duke University, points out that investors and economists learned a hard lesson in 2008-2009, as many had dismissed the earlier yield-curve warning.

The inversion could cause a recession in two ways. First, it could become a self-fulfilling prophecy, as investors and CEOs see the inverted yield curve as a signal to cut back risk-taking in expectation of recession, creating the very economic weakness they were worrying about. Second, an inverted curve hurts the basic business model of banks, that of borrowing short-term and lending long-term, hitting profits and reducing lending—again, bad news for growth.

The inverted curve could also help explain why the recession hasn’t—yet—hit. The combination of an inverted curve and falling stock prices put a lid on the postpandemic boom in corporate investment.

When the curve inverted before the 1990 and 2008-2009 recessions, corporate investment went up, as the economy went into a final growth phase. This time CEOs and CFOs with an eye on the curve might have exercised some caution, helping moderate the boom and so extending the period of growth. Rather than talk ourselves into recession, maybe we merely talked ourselves out of a boom.

The key lesson of the yield curve is that inversion doesn’t guarantee recession, but it is foolish to dismiss it.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES Broadridge Investor Communication Solutions, Inc. does not provide investment, tax, legal, or retirement advice or recommendations. The information presented here is not specific to any individual's personal circumstances. To the extent that this material concerns tax matters, it is not intended or written to be used, and cannot be used, by a taxpayer for the purpose of avoiding penalties that may be imposed by law. Each taxpayer should seek independent advice from a tax professional based on his or her individual circumstances. These materials are provided for general information and educational purposes based upon publicly available information from sources believed to be reliable — we cannot assure the accuracy or completeness of these materials. The information in these materials may change at any time and without notice.

Prepared by Broadridge Investor Communication Solutions, Inc. Copyright 2021.